How a painting sits

3/17/2025

A painting is never static. It changes depending on where it exists, how it is viewed, and the environment surrounding it. This impermanence fascinates me, how a painting can be one thing in a white-walled gallery and something entirely different when placed in an unexpected space. A shift in the environment alters not just the painting’s presence but its accessibility, meaning, and perception.

I’ve been thinking about this a lot since watching a conversation between Katharina Grosse and Sarah Sze, moderated by Hans Ulrich Obrist at Art Basel. They spoke about how paintings, when placed outdoors, ‘belong to everyone and no one.’ That phrase has been lingering with me. It captures something I’ve often felt but hadn’t quite articulated: how a work can shed its attachments to status, authorship, and intent when it leaves the gallery behind.

Source: Katharina Grosse, Psychylustro, Philadelphia, USA, 2014

In a gallery, art is in a structured environment, both physically and conceptually. It invites a specific type of viewer, often those with an existing interest or background in the arts. The space encourages slow looking, discussion, and analysis. But outside the gallery, a painting becomes something else. A work placed in a public space, on a beach, a mountain, or in a forest belongs to no one and everyone. The artist’s name, status, and intent dissolve, leaving behind only the raw encounter between the work and the viewer. Seen on a daily commute or a casual walk, the painting is no longer something to be studied; it is simply something to be experienced. Does this make the encounter more honest? More immediate?

Katharina Grosse, one of my favourite artists for her philosophy of art and theories of space and time, explores this beautifully. Her large-scale, site-responsive paintings transform entire environments, fields, abandoned buildings, even train tracks, blurring the boundaries between painting and space. Her work asks: does a painting adapt to its surroundings, or does it reshape them? When colour spills across walls, rocks, and landscapes, is it still a painting, or does it become something else entirely?

This raises a question for artists:

Does a painting lose its integrity when placed in an unpredictable space? Or does it gain something new, an evolving dialogue between medium, environment, and audience? Does a work need a fixed context, or should it be free to shift and change, taking on different meanings in different places?

The conversation between Grosse and Sze, that I first watched a few years ago now, and more recently, has stuck with me, prompting these questions in my own practice. I find myself wondering how my own work shifts in different contexts and spaces, leaving plenty of room for alternate response, connection and engagement. So maybe a painting’s truest self is when it’s raw, free of attachments or preconceived judgement, passing by like a leaf in the wind.

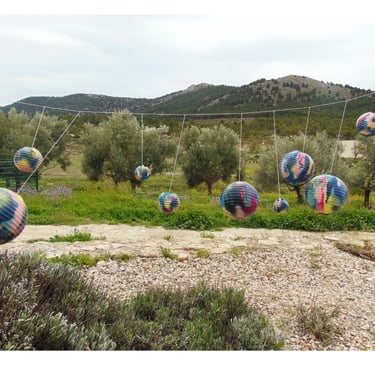

Source: Annie Ashwell, What is painting II, temporary installation, Velez Blanco, Spain, 2022